Making How to Clean a Hippopotamus

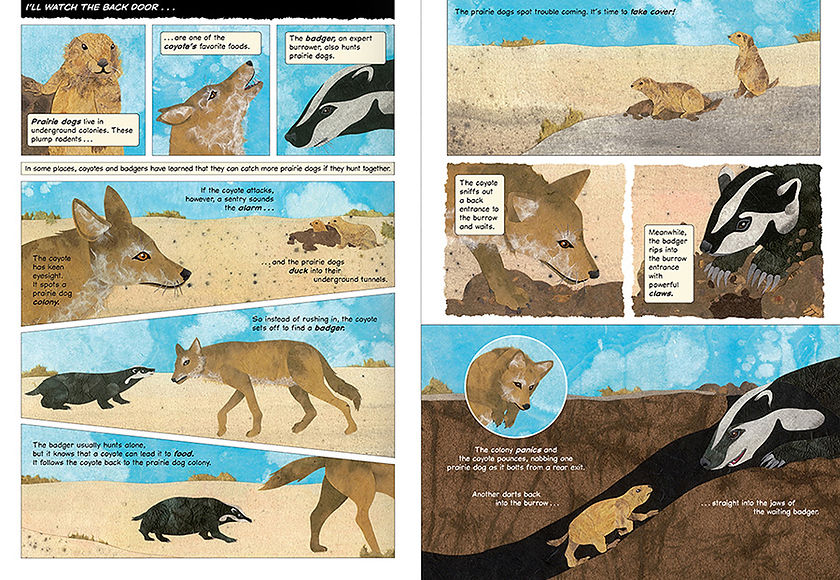

This gave us the idea of doing a book about animal symbiosis, specifically mutualism, which is a type of symbiosis in which both animals benefit from their relationship. We began to research the topic. We have a lot of books about animals in our studio. We also use the public library and the internet.

I like to write my first draft by hand in a notebook. To me, text written on the computer tends to look too finished, and it's not as easy to cross things out or simply start over. For subsequent drafts I put the text into a word processor, print it out, and make further edits by hand. I go through at least a dozen drafts before the copy is final.

What is Science?

For most of human history, people had no way to make sense of many of the things they saw and experienced. Fire, storms, drought, the seasons — even the rising and setting of the sun — were caused by mysterious forces. Natural events, especially those that affected our survival, were explained by myth, magic, and superstition. This view of the world often made people fearful. It sometimes led to terrible things, such as sacrificing a child to insure a good harvest.

About 2,500 years ago a few people began to look at the world differently. They were inventing science — a new way of questioning and explaining natural phenomena. Science starts with observing the world and noticing something that demands an explanation. Why does the sun rise in the east every morning and set in the west every evening? For some, the story of a god driving a fiery chariot across the sky wasn't a satisfactory answer. They noticed that the moon and stars, as well as the sun, passed across the sky in a daily cycle. Was it possible that the sun was a large, hot object, and that it and the rest of the heavens circled the earth? This was a theory — an idea that explained what was observed. This theory lasted almost two thousand years. There was a problem, however. The motion of some of the stars — planets, we now know — did not follow the rules that the theory predicted. They behaved in odd ways, traveling along complicated paths in the sky, sometimes even moving backwards. The theory that placed the earth in the center of the universe grew increasingly complex as it tried to explain these observations. But it was the best explanation that anyone could come up with for a long time. As more detailed observations of the sky were made, however, more and more complicated adjustments were needed to explain what people were seeing.

Around 1500, a Polish scientist named Copernicus proposed a new theory. Perhaps the earth was not at the center of the universe after all. What if the earth, its moon, and the rest of the planets circled the sun? This was a controversial idea, but it explained what was being observed in a more elegant way. Many people rejected this new theory, but because it made predictions that could be tested and shown to be accurate, other scientists eventually accepted it. This illustrates something important about science and scientific theories. Science is a process, not a set of facts. And a theory is not a fact. It’s a way to explain the way the world works, and it can always be proven wrong and replaced if a better explanation is proposed.

Challenges to Science

These days there is a lot of confusion about the nature of science. The current debate about the theory of evolution and how it is taught is one example. A few school boards, responding to culture-war pressures, have added stickers to their science books that say “evolution is only a theory.” If these stickers were more comprehensive, they’d also say “gravity is only a theory,” “the idea that matter is composed of atoms” is only a theory, and so on. The theory of gravity is well supported by many observations. It predicts that people, rocks, and houses will remain resting firmly on the ground. There is no guarantee, however, that everything won’t float off into space tomorrow. It’s just that there are no observations that make this seem likely. In the same way, the theory of evolution does an excellent job of explaining the development of different kinds of living things and predicting what will happen to them in different situations. No other scientific theory has been proposed that explains the development of life. Creationism and intelligent design are not science — they offer no testable predictions.

Believing in a religious or supernatural explanation of the world is a personal choice — it’s not, in my mind, right or wrong. It is not science, however. One reason the evolution debate is so important is because of the way it’s fostered a misunderstanding of what science is and how it works. Creationists and intelligent design advocates have presented elaborate arguments for their beliefs that, confusingly, appropriate the language of science. The drama around the theory of evolution has also resulted in a great deal of self-censorship by educators and administrators unwilling to deal with a controversy that really has nothing to do with science.

Along with some of the cultural and political barriers to teaching science, many schools have de-emphasized it (along with music, art, history, civics, and sports) because of policies that reward or punish a school for their students’ performance on standardized tests of math and English. I believe that this is a case of generally good intentions with unintended harmful consequences.

Science and Wonder

There is a popular misconception of the scientist as coldly logical, unmoved by beauty, and lost in reams of data and numbers. From this perspective, science is the opposite of art or poetry. There’s also a commonly held view of science as boring and difficult. The difficult part can be accurate. But science is anything but boring. Unfortunately, in my view, it's not uncommon for well-meaning educators to present science and scientists to children as wacky or goofy (think: wild hair, thick glasses, and a disheveled lab coat). I find this patronizing. There is real satisfaction — for child and adult — in doing the sometimes challenging work of understanding a scientific concept.

The biologist Richard Dawkins has said “It has become almost a cliché to remark that nobody boasts of ignorance of literature, but it is socially acceptable to boast ignorance of science.” That’s too bad, because science has the ability to show us a universe more beautiful and amazing than any we could imagine — entire galaxies disappearing into massive black holes; enormous stars creating the elements our bodies are made of as they destroy themselves in explosions of unbelievable force; living things made of trillions of cells that interact with exquisite precision.

My own view is that the more we understand about what the universe is and how it works, the greater our appreciation of the beauty and wonder of the world, of each other, and of us being able to think about it all.

Science — Good and Bad

Science is not good or bad. It is a tool, like a piece of wood that our ancestors could use to build a fire for warmth or as a club to bash someone’s head in. Science is a very powerful tool. Used to do bad, it can cause terrible harm. Used to do good, it can ease suffering and make our lives much richer. This is why it’s so important for children to understand what science is and how it works. They will be asked to make science-based decisions — about energy, biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and things we have not yet thought of — that can have both good and bad consequences. Because the scientific process teaches us to not accept things at their face value, to ask questions, and to demand evidence, it will be invaluable to our children as they confront an increasingly complex world.

Answers to some of the questions that children (and adults) frequently ask:

How many books have you written?

As of Spring 2021, about sixty. Twenty-four of them were written with my wife and co-author Robin Page. I’ve written one book that was illustrated by another artist. I’ve also illustrated about twenty-five books that were written by other authors.

Where do you get your ideas for books?

Many of my early books were written in response to questions my own children asked (Robin and I have three — two boys and a girl — who are now grown up). Others were inspired by something one of us read or saw in a nature documentary. And some originated with observing animals in zoos or in their natural habitats. All of our books begin with a question: How does a hummingbird fly backwards? What killed the dinosaurs? Why do animals come in so many shapes and colors? Robin and I each keep lists of book ideas that we share with each other.

How long does it take to make a book?

It’s usually about two years from the time I start work on a book to holding a printed copy. But I’m working on more than one book at a time, and much of that two years is waiting for an editor to comment on the text or a printer to photograph the art and produce the book. If we take out the waiting time, it’s probably four to six months of solid work to make a book.

How long does it take to make an illustration?

My illustrations are cut- and torn-paper collages. I don’t draw or paint on the paper — every picture is composed of separate pieces of paper. Naturally, the time required to complete an illustration varies. A creature with lots of spots, scales, or spines might take several days. Simpler subjects can sometimes be completed in a few hours. Often the research and preliminary sketches take more time than the finished illustration.

What’s your favorite animal?

This question has two answers. If it’s an animal I’m going to spend time with, it would be a dog (we have two golden retrievers). If it’s a wild animal, I’m especially partial to the beauty, grace, and power of the Siberian tiger.

What’s your favorite book (that you’ve written)?

I often say it’s the one I’m working on at the time, because there’s always the chance that it will turn out to be the best one I’ve done. Of the books that have been published, I’d say The Animal Book.

What’s your favorite book by another author?

In the world of picture books, I’d choose Gorky Rises, by William Steig. Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, by the same author, is a close second.

Have you ever written a chapter book?

No, but I keep thinking that someday I'd like to try.

When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

A scientist. Either an oceanographer or a paleontologist (a scientist who studies fossils).

hummingbird

dogs and cats

a portrait of the author

in his studio

A Partial List of Book Awards (and the number times received)

Washington Post/Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award (for a body of work)

Randolph Caldecott Medal Honor Book (for What Do You Do with a Tail Like This?)

Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards: Winner, Nonfiction (for Top of the World)

Boston Globe Horn Book Nonfiction Honor Book (2)

ALA Notable Book (7)

New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books (2)

Orbis Pictus Honor Book (3)

Orbis Pictus Recommended Books (3)

AAAS/Subaru SB&F Prize for Excellence in Children’s Books

AAAS/Subaru SB&F Prize finalist (3)

Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K-12 (3)

Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts, NCTE (4)

Cooperative Children’s Book Center Choices (6)

A New York Public Library’s 100 Titles for Reading and Sharing (6)

Chicago Public Library Best-of-the Best (8)

Bank Street Best Children’s Books of the Year (15)

The Society of Illustrators Original Art show Silver Award

The Society of Illustrators Original Art show (12)

Booklinks Lasting Connections Selection (3)

Junior Library Guild Top 10 Books for Youth

Junior Library Guild Selection (13)

La Science se Livre Literary Prize, Children’s Categorey

Theodor Seuss Geisel Award

The John Burroughs Riverby Award

My books have been translated into nineteen languages.

Children's Art

One of the unexpected pleasures of writing for children is receiving mail from my readers, which often includes collages or drawings based on one of my books (or the animals in them).

crocodile

panda

condor

hummingbird

honeybee

a portrait of the author in his studio